Side Project of a Side Project

January 02, 2026 · 2371 words

Before switching to a platform engineering role within the AI Engineering Group earlier this year, I spent 9 months working on RAG with financial research documents.

The main lesson I learnt from this experience is that you have to solve retrieval first before you solve RAG. To achieve a desired user experience, you need to own (or at least be able to contribute to) the entire pipeline from indexing to retrieval to reranking to generation, rather than simply adding a generation step on top of an existing search system.

In this post, I will describe my personal journey of trying to build a search system for company documents in the UK, and how I ended up writing a Python client for Apache Solr.

Search Pipeline

With the above lesson in mind, I thought about building a sandbox environment where I could tune different search pipeline configurations against different sets of requirements. As a starting point, for example, I’d ask myself:

- How often do I need to ingest new documents?

- How fast should search be?

- What is the distribution of keywords like in the document domain?

Answers to these questions will influence the system architecture, often with tradeoffs across different components.

For instance, the frequency and lengths of new documents inform whether we can apply compute-heavy document understanding or enrichment steps. We cannot spend multiple seconds ingesting a single document if new documents keep arriving while processing it.

If this requirement is not strict, then we can potentially afford to extract metadata from documents such as named entities or rephrasing some of the keywords and setting up specific fields to search over for BM25, which would improve both latency and relevance for sparse retrieval.

Keyword distribution also has consequences on how we handle ambiguity and vocabulary mismatch between the user query space and the document domain, with implications for the choice of the embedding algorithm, vector search databases, and vector search algorithms.

The Side Project

The actual project I wanted to work on was a better search system for company information on UK startups using the Document API from Companies House 1. This was motivated by my personal experience that startups are generally much less transparent when things are not going well, and that the current user experience of Companies House is not ideal in terms of document discoverability and readability.

Providing a better search system for such information could potentially help alleviate the pain point of not having enough realistic information on company financials and governance structures prior to joining a startup. This assumes the existence of documents disclosing such information in the Companies House database already. This is often the case after startups raise Series A or Series B rounds when they typically accelerate their hiring efforts.

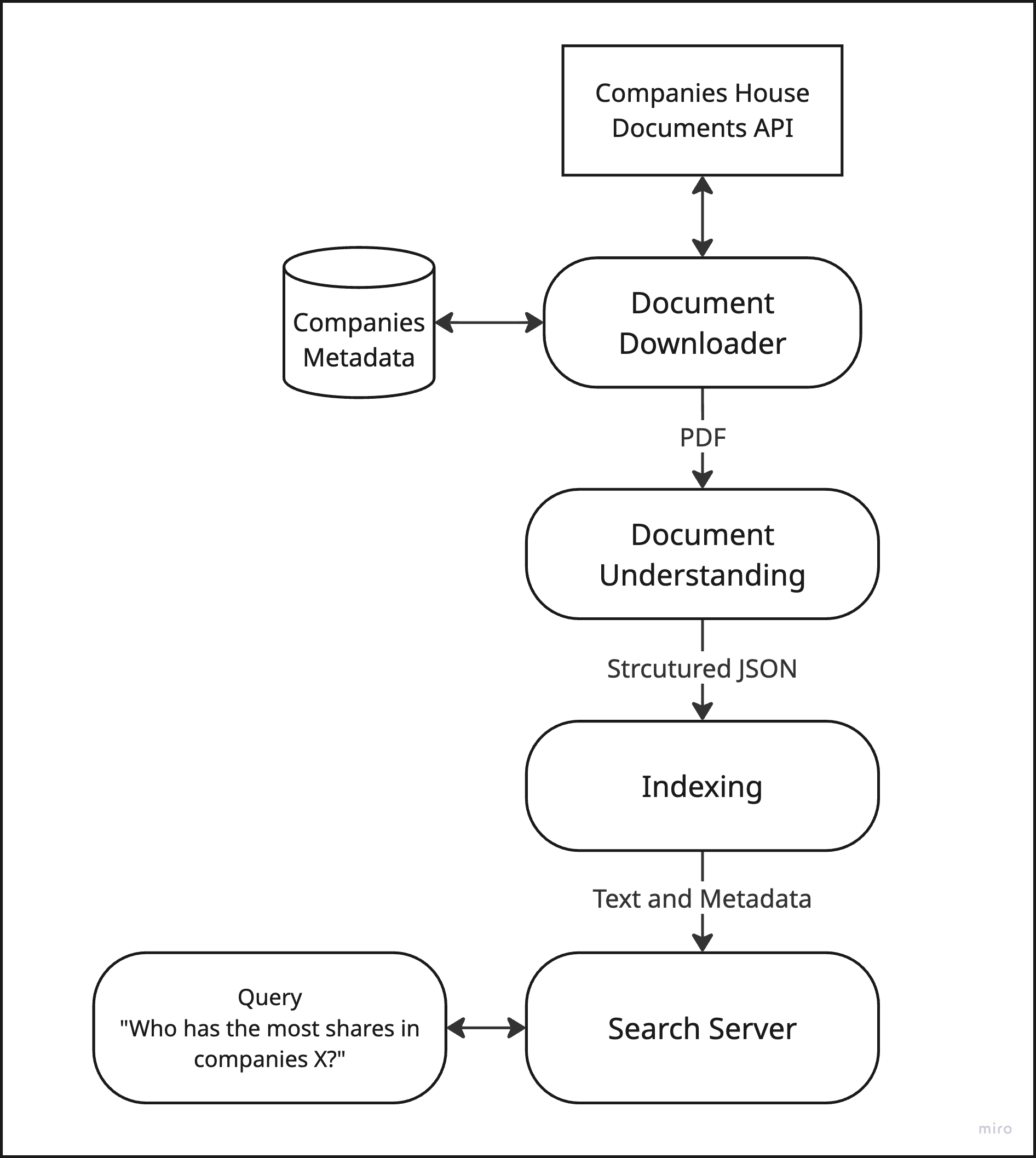

In Companies House, the documents are almost always indexed as PDFs and the frequency of document updates is generally low, say, no more than one document per day per company. This necessitates (1) a document understanding step from PDF to some form of structure that can be indexed into the search system and (2) some flexibility on latency to run this step, opening up the possibility of using something more advanced than simple PDF parsing, such as vision-language model-based SmolDocling.

With those requirements, I came up with the following diagram with necessary components for setting up the search pipeline.

Searching for Search Servers

I started to look for the libraries and technologies to fill in those components in the diagram above, and considered multiple options for the search server. With the exception of Meilisearch which is built in Rust, the mainstream enterprise search options are Elasticsearch, OpenSearch, and Apache Solr, which are all built on Apache Lucene. I had experience using Apache Solr in a previous RAG project and decided to stick with it due to its robust sparse-retrieval performance and ecosystem maturity.

This HackerNews comment from tekkk on Aug 16, 2020 echoes my sentiment on Solr:

Solr is one of those technologies which works but isn’t really glorious to use and is a bit stuffy with its XML configurations and Java interfaces. It’s a bit of a shame, because search engines are so popular nowadays and everybody seems to be fixated on using ElasticSearch, which from what I’ve read and heard is resource-hungry and not really suited for simple text-search.

and note that this comment predates the rise of LLMs which subsequently led to the popularity in RAG and has since invited a number of ML practitioners who are typically not familiar with the Java ecosystem, including myself.

I believe this is the primary point of friction where the interface becomes the main bottleneck for developing a search system. For example, the de facto official Python client for Apache Solr is pysolr, which has been around for well over a decade and is implemented in one 1500-line Python file.

This unfortunately falls short of expectations for a modern Python experience. For instance, pysolr does not support async operations at all, making concurrent queries inefficient compared to libraries that leverage Python’s async features. Indexing documents is also less ergonomic, and there is no built-in type safety, which can lead to runtime errors and make integration with typed codebases more challenging.

Another source of confusion for new users is that pysolr exposes Solr’s query syntax directly. Parameters like q, fl, and qf are somewhat terse abbreviations for a new user, and the relationship between query parameters and query parsers is not clearly documented or enforced by the client. This can make it difficult to understand the hierarchy and structure of queries, especially for those unfamiliar with Solr’s internals.

Let’s take a look at an actual example. The following snippet sets up a Solr client and uses Extended DisMax Parser to find the keyword “preference shares” (prioritizing the summary field matches over the content field) and returns the results grouped by company_name field with a limit of 3 documents per group.

As a prerequisite, Solr’s search request is constructed as HTTP query parameters and is sent as a GET request to a given collection of documents. In pysolr, those are set directly as Python dictionaries as follows.

from pysolr import Solr

solr = Solr('http://localhost:8983/solr/company_documents', timeout=10)

params = {

'defType': 'edismax',

'q': 'preference shares',

'qf': 'summary^2.0 content^1.0',

'group': 'true',

'group.field': 'company_name',

'group.limit': 3,

'group.ngroups': 'true'

}

results = solr.search(**params)

The response here is an untyped dictionary that the user has to parse and validate manually, and it’s also hard to understand all the fields needed in the params and how they interact with each other.

Writing a New Client

This is the point where I decided to rewrite the Python client from scratch with a modern setup with full type-safety and async support. My aim of building this client was to provide a better developer experience with a clearer interface with full IDE support which also doubles as a wrapper around the official Solr Query Guide 2, and having a standardised way to provide the document class in the search responses using Pydantic models.

I named this client Taiyo after the Japanese translation of the word sun which Solr-related projects often get the inspiration from, such as sunburned which is another Python client. The full documentation is available in Taiyo Docs and the source code is available on GitHub.

Going back to the Extended DisMax query example. Taiyo now allows you to set up a query parser like the following:

from taiyo.params import GroupParamsConfig

from taiyo.parsers import ExtendedDisMaxQueryParser

parser = ExtendedDisMaxQueryParser(

query="preference shares",

query_fields={"summary": 2.0, "content": 1.0},

configs=[

GroupParamsConfig(by="company_name", limit=3, ngroups=True)

],

)

with GroupParamsConfig object passed in as a config object and each field autocompleted in the IDE with documentation referenced from the official query guide.

Alternatively, it’s also possible to set up the same exact query with a pandas-like chaining on the parser object:

from taiyo.parsers import ExtendedDisMaxQueryParser

parser = ExtendedDisMaxQueryParser(

query="preference shares",

query_fields={"summary": 2.0, "content": 1.0}

).group(

by="company_name",

limit=3,

ngroups=True

)

Whether you use config objects or method chaining is a matter of personal preference or complexity. If you need a highly custom/multiple layers of configuration, you might want to opt for config objects that can be set up in different places (i.e in a iteration loop or loaded from a separate file).

If a potential user is hesitant on switching to a new client, they can also make use of Taiyo’s query parsers which serialises into Python dictionaries that other clients like pysolr accepts.

from taiyo.parsers import StandardParser

parser = StandardParser(

query="preference shares",

query_operator="OR",

filter_queries=["created_at:[2025-01-01 TO *]"],

rows=10,

)

# Build query parameters as dictionary

params = parser.build()

# {

# 'q': 'preference shares',

# 'q.op': 'OR',

# 'fq': ['created_at:[2025-01-01 TO *]'],

# 'rows': 10,

# 'defType': 'lucene'

# }

# Use with httpx or any HTTP library

import httpx

response = httpx.get(

"http://localhost:8983/solr/company_documents/select",

params=params

)

You can also make use of the document model when searching for documents. For instance, if you set up the following CompanyDocument class derived from taiyo.SolrDocument, then you can specify this in the parser such that the responses are fully typed.

from taiyo import StandardParser, SolrDocument

class CompanyDocument(SolrDocument):

document_id: str

company_name: str

company_number: int

category: str

created_at: str

summary: str

content: str

# Search returns typed results

parser = StandardParser(query="preference shares")

results = client.search(parser, document_model=CompanyDocument)

# Access typed company documents

for doc in results.docs:

print(f"{doc.category} document for {doc.company_name} ({doc.company_number})")

print(f"Summary: {doc.summary}")

With the async support with httpx, you can also index typed documents asynchronously as follows:

import asyncio

from taiyo import AsyncSolrClient, SolrDocument

async def ingest(docs: list[CompanyDocument]):

async with AsyncSolrClient("http://localhost:8983/solr") as client:

client.set_collection("company_documents")

# Split into batches and process concurrently

batch_size = 100

batches = [docs[i:i + batch_size] for i in range(0, len(docs), batch_size)]

# Index all batches concurrently

await asyncio.gather(*[client.add(batch, commit=False) for batch in batches])

await client.commit()

docs = ...

asyncio.run(ingest(docs))

Making something I want

There are several lines of work planned, including supporting more query parsers such as XML parsers, along with clearer documentation. Also note that this client doesn’t abstract away the Lucene query syntax in the query parameter, which could be provided as a utility function in this library, should I find an intuitive interface.

The inevitable next step is to build out the original side project I set out to work on, which is to build a better full-text search system for company documents. The best thing about this client is that it would not be the end of the world if nobody finds it useful, as long as it helps me on my original journey and I can find value in it myself.

YC’s famous motto Make something people want 3 is great advice for building venture-scale companies, but making something I want is more than enough as a heuristic for building side projects while keeping a full-time job, which was definitely the case for Visprex in 2024 and Taiyo in 2025. I’m looking forward to writing about another side project this year, hopefully more often than in the past two years.